1956

sun and rain on the 69th anniversary

1956 - the numbers used to send a frisson up every Hungarian spine. In 1986 or 1987, I was sitting in a taxi when the taxi metre hit that number - the driver nodded to me, to make sure I had seen it. The same happened with friends when you passed a roadsign announcing 56 km to the next city. It was a magic number, one that Hungarians were proud of. That made it a very awkward number for the ruling Hungarian Socialist Workers Party (HSWP). The revolutionary potential of the anniversary was woven into the fabric of the dramatic political changes of 1988 and 1989, and the story-telling around it. If 1956 was a revolution, an alarmed János Berecz, head of agitation and propaganda in the HSWP remarked, ‘then we would be counter-revolutionaries!’

25 October 1956, Budapest. FORTEPAN / Gyula Nagy

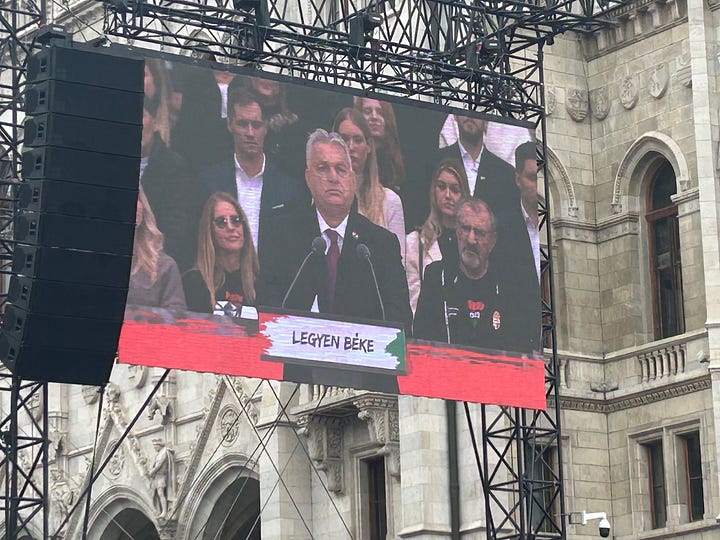

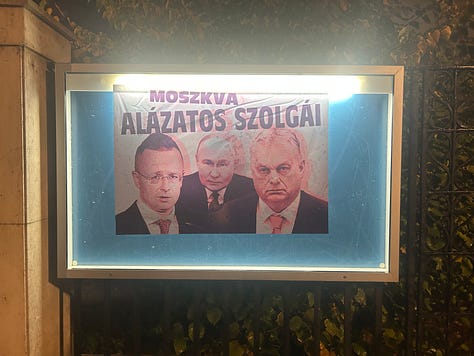

This year’s anniversary was marked, in traditional Hungarian polarised fashion, by a march of Orbán supporters to Kossuth Square in the morning sunshine, and of opposition Tisza party supporters of Péter Magyar to Heroes Square in the pouring rain in the afternoon. Most waved Hungarian flags - what a great day for flag-sellers! They could put out their wares, from 8 am to 8 pm.

The Prime Minister and his Challenger, 23 October 2025

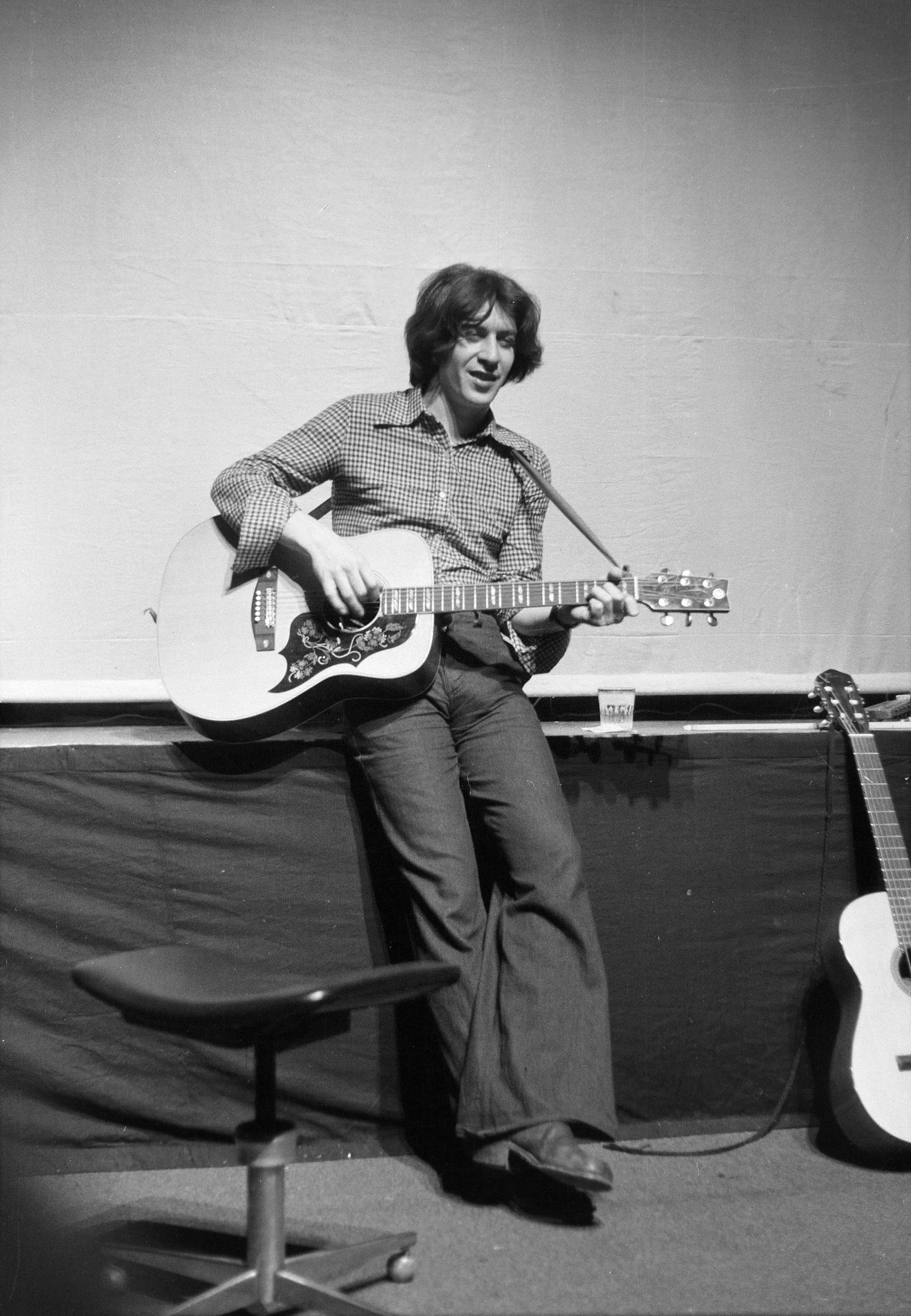

Recordings of the great Hungarian balladeer Tamás Cseh poured from the loudspeakers at both rallies.

Tamás Cseh in 1975, Fortepan / Vadász Ágnes

Hányon kipusztultak/ How many perished - from the 1979 album Frontátvonulás

You know that over the years, many of us

have perished,

and not the worst ones,

but above our tile-covered roofs,

the sun still rises.

How many have left,

and not just the newcomers,

but above our tile-covered roofs,

the clouds come and go.

But now we are here,

listening to songs,

singing about

how many have died,

how many have rotted away,

how many have gone to hell,

and not exactly the rotten ones.

Above the tile-covered roofs,

the sun comes and goes,

and now I sing this song here,

about a time unfavorable to youth,

an unfavorable time,

clouds passing left and right and then rain,

a rain that washes everything away…

Many analyses of the size, messages, and meaning of this year’s marches have already been published. For what it’s worth, after reporting on innumerable rallies on those same bridges and echoing streets for the past 40 years, I reckon that while there was an impressive turnout for both, there were more people, and more young people, at the Tisza Party gathering than at the Fidesz one. Just one other observation: the majority of the random people I spoke to at the beginning of the Fidesz march, had arrived on buses from Romania and Serbia. But in the square in front of Parliament, there seemed a lot less people than during the march over Margit bridge. My guess is that many people did their bit by marching from Buda to Pest, then quietly slipped away to do some shopping, before the long bus journey home in the afternoon. If so, that doesn’t bode well for Viktor Orbán in the election next April. But who knows?

Here is my account of 23 October 1986, from my book ‘89 The Unfinished Revolution - Power and Powerlessness in Eastern Europe.

At six in the evening on 23 October, a sixteen year old girl laid a small Hungarian flag at the foot of the statue to Józef Bem. The ever-vigilant secret police pounced, wrote down her identity details, and let her go. Then the western journalists surrounded her. She seemed beautifully unperturbed by either. She had put the flag there partly for her father , who had taken part in the revolution, she said. But mainly for herself.

In a tumbledown two-storey wooden house in the suburb of Békásmegyer in the north-west of Budapest about eighty people squeezed into a room to mark the anniversary. Candles were placed in the windows as a symbol of mourning for the dead. Sándor Rácz, a young workers’ leader from 1956, in black suit and tie, reminded those present that the freedom which the people had fought for in 1956 had still not been achieved. Solemn hymns were sung. Then anoint statement was read out, linking the 1953 protest in East Berlin’s Stalinallee with 1956 in Hungary, 1968 in Czechoslovakia and 1980 in Poland.

We took notes, and broadcasted it around the world.

The next day, I went with my BBC colleague David Blow to the city cemetery, in the distant suburb of Rákoskeresztúr, near the airport. We parked the car on the edge of a nearby industrial estate, and climbed a half-broken concrete fence into a remote corner of the cemetery, narrowly missing a dead Alsatian.

This was Plot 301, where those executed after the revolution were buried beside circus and zoo animals. It said something for the strangeness of Hungarian history - the remains of the martyrs resting uneasily among exotic beasts, lions and bears and elephants.

It was dusk when we got there, never the best time of day in a cemetery. But we were not alone. Parked some distance away was a green Lada with the AJ registration plates of state security. And near it, a tall thin man and a short fat one were loitering, like in a Cold War film. They watched us sideways on, like birds, and appeared to be pretending not to have seen us. So we ignored them too, and set about exploring the undergrowth. There were row after row of unmarked graves, overgrown with hemp plants. A few had been cleared, and planted with makeshift crosses and flowers. When the revolutionaries were executed, between 1957 and 1962, several mothers of the victims managed to follow the vehicle at a distance, or bribe the guards into telling them where their children were buried.

The best-kept of the graves had a large green bush planted on it, which had been scattered with white carnations. We took notes and photographs. Then sidled over to our watchers. ‘Any idea who is buried here?’ I asked the tall man in the leather jacket. He smiled, horribly, displaying long yellow teeth to match his long yellow face and yellow fingers. ‘Among others, Imre Nagy,’ he replied. To the best of my knowledge, it was the first time a state employee in communist Hungary had ever confirmed the whereabouts of the mortal remains of the leader of the revolution. We thanked them and left hurriedly, through our hole in the fence.

Imre Nagy on the right, taking part in the grape harvest, Badacsonytomaj, 22 October 1956. One of my favourite pictures of him. Late October is always a beautiful, melancholy time of year, on the northern shore of Lake Balaton.

Looking southwest, towards Badacsonytomaj, from the Tihany peninsula, 22 October 2022.

Imre Nagy was called back to the capital by the crowds, and became the reluctant leader of the revolution. He was executed by hanging in the early morning of 16 June 1958, alongside Pál Maléter (Minister of Defense) and Miklós Gimes (journalist). At his secret trial, he said:

„Másként nem cselekedhettem, a nép bizalmát nem árulhattam el.”

“I could not have acted otherwise; I could not betray the trust of the people.”

Interesting, thanks. I knew nothing of Imre Nagy but your piece prompted me to find out more. A tragic political life (and death), and full of irony in the context of the current polarisation of left and right. An old school Marxist communist, encouraged by Krushchev's denunciation of Stalin to lead the resistance, but then encouraged the army not to fight and tried to lead a reformed governement, but in the end sided with the people and was executed as a lesson to other leaders of Sobiet republics. The lesson from history is that revolution is force of nature, and the military tides and political currents at work can overcome the efforts one one man, and can overwhelm any hope that a single leader could steer events toward a peaceful or independent outcome. And strange that Orban recognised the contribution of a Marxist-Leninist to an independent Hungary. Much food for thought in trying to untangle what is significant and what trivial in the current debate... Thanks again.

I think your comparison of the two rallies was a bit tame. Orban's "Peace march" and Magyar's "National March" were so contrasting. The peace March was Magyar's, far simpler and FAR bigger with him opting for a small open stage in the MIDDLE of the people in Heroes Square, rather than a huge construction outside Parliament. Orban's focus was on war and Ukraine and Brussels, Magyar's was on unity, equality and hope for the future. The response to journalists' questions was very different as well from those in the two rallies, with the Fidesz people still solving the future by fighting other Hungarians ... and not forgetting those at Orban's were given free transport, and vouchers to attend, whilst Magyar's came of their own accord and at their own expense.