A Conversation in the Mountains

On Paul Celan, Osip Mandelstam, and Ivan Illich

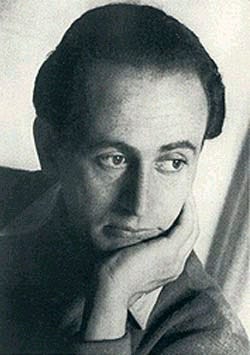

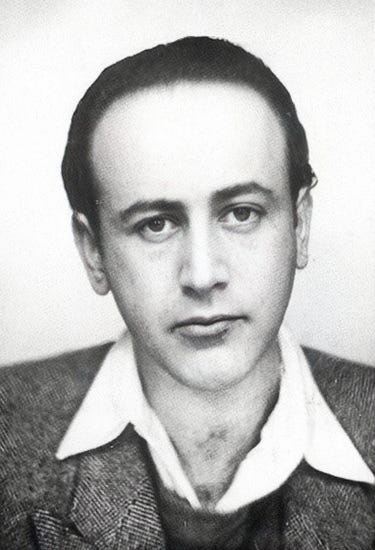

Pass photo of Paul Antschel, 1938

I first came across the work of the Jewish poet Paul Celan in the frontispiece to a book by the Canadian journalist David Cayley about the Austrian priest, philosopher and activist, Ivan Illich:

Into the rivers north of the future

I cast out the net, that you

hesitantly burden with stone-engraved

shadows.

The poem, which Illich loved, speaks of ‘a hoped-for “not-yet,” a time and place which cannot be reached by simply projecting from the present, since it lies north of the future. And, even in these inaccessible waters, the nets that can be cast out are “burdened with stone-engraved shadows,” the weight of all that has been.

For Celan, who came from the Romanian-Ukrainian city of Czernowitz/ Cernăuți/ Chernivtsi, and whose mother, father and many relatives were murdered by the Nazis, the burden of the past, and what was done to his people, weighs particularly heavily. After the war, he moved first to Bucharest, then Vienna, then Paris, where he committed suicide by drowning himself in the River Seine, aged 49, in 1970.

‘To hell with the future…’ Illich said in an interview in the winter of 1986. ‘It’s a man-eating idol. Institutions have a future…but people have no future. People have only hope.’

This post will focus on Paul Celan, who wrote in German - the tongue of the people who tried to exterminate his people; and on Osip Mandelstam, the Russian poet whom Celan translated into German, and whose presence on earth Stalin could not tolerate. But the sting, or kiss in the tail of the post, I will leave to Illich.

Interesting to celebrate three remarkable men, in a media world so concentrated on celebrating remarkable women.

Celan, Mandelstam, Illich

I write about Celan in my book Walking Europe’s Last Wilderness, in Chapter 14, about Bukovina. The main sources for this post are John Felstiner’s Paul Celan - Poet, Survivor, Jew and Rivers North of the Future - The Testament of Ivan Illich, as told to David Cayley. Illich’s ancestors, on his mother’s side, were also Jews from Chernivtsi.

It’s falling, mother, snow in the Ukraine:

The Saviour’s crown a thousand grains of grief.

Here all my tears reach out to you in vain.

One proud mute glance is all of my relief…

Celan, whose original name was Antschel (Celan is a rearrangement of the Romanian spelling ‘Ancel’) tried in vain to persuade his parents to flee, when the Nazis occupied the city, and forced all Jews into a ghetto. He was not at home when they deported the Jews to a concentration camp in Transdniestr, where up to 120,000 Romanian Jews died. He never saw them again.

Celan wrote all his life in German, painfully re-inventing a language corrupted by the experience of totalitarianism.

"the German I speak is not the same as the language the German people are speaking here,” he once wrote to his wife, Gisèle.

In his acceptance speech for the Bremen Literature Prize (1958), he said:

‘Only one thing remained reachable, close and secure amid all losses: language. Yes, language. In spite of everything, it remained secure against loss. But it had to go through its own lack of answers, through terrifying silence, through the thousand darknesses of murderous speech. It went through. It gave me no words for what was happening, but went through it. Went through and could resurface, 'enriched' by it all.’

As he wrestled with the language of his mother, who brought him up with a love for the language of Rilke and Hölderlin, and of those who shot her, he invented words, toying with a language easily toyed with: Fadensonnen, meaning ‘Threadsuns,’ or Lichtzwang ‘the compulsion of light.’

Paul Celan, the polyglot survivor, who survived the Nazis then escaped the Soviets, lived first in Bucharest, then Vienna, then settled in Paris, translated poetry all his life. He was particularly taken by Osip Mandelstam, the Russian poet murdered by Stalin in the gulag in 1938.

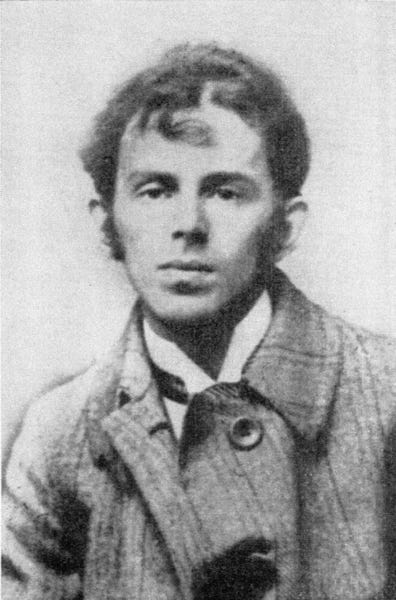

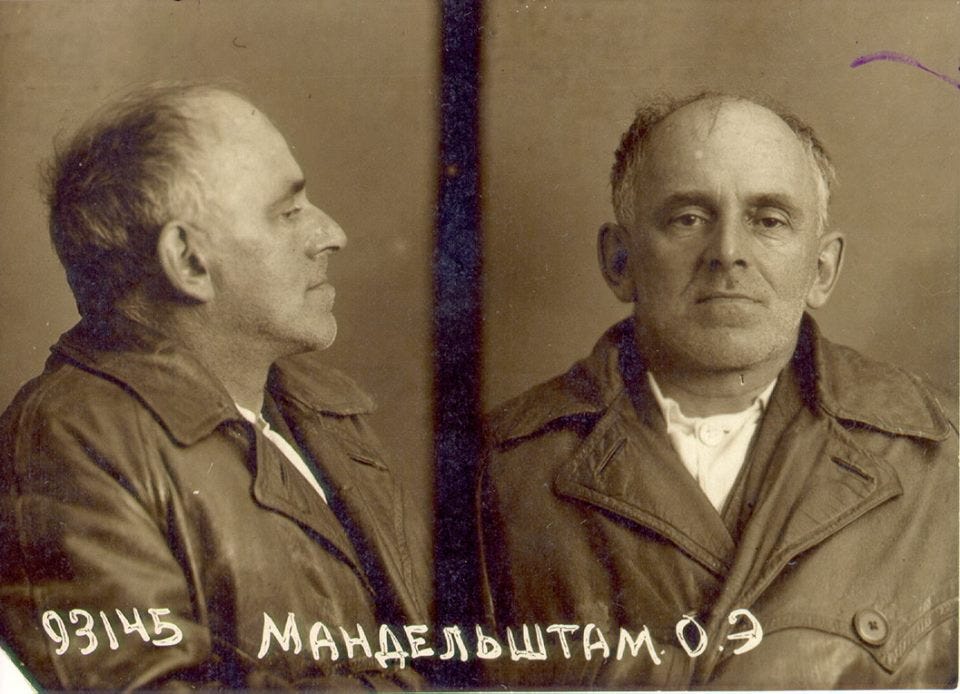

NKVD (Soviet secret police) photo of Mandelstam, in the year of his death, 1938

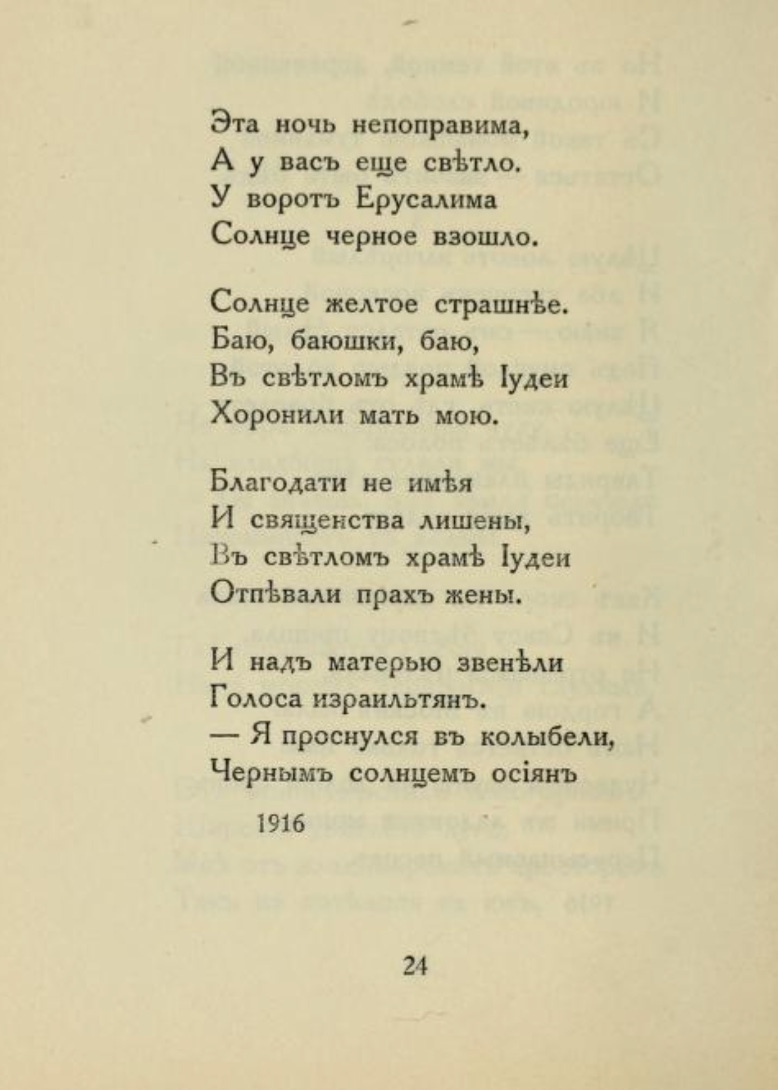

In 1916, the 25 year old Mandelstam wrote a poem about the death of his mother (first published in Tristia, in 1925).

The full text of Tristia, in Russian

A literal translation of the Russian, quoted by Felstiner, reads:

“And over my mother rang out

voices of the Israelites

I awoke in the cradle

lit by a black sun”

But Celan translates this into German as:

“Jewish voices, not gone silent

Mother, they resound.

I awake inside my cradle,

sunblack beams all round.”

Translations of poems are always ‘re-versions’, but Celan does something remarkable here - he takes a 1916 poem by a fellow Jew (whose name means ‘the stem of an almond’), and moves it 42 years forward in time to 1958, after the Holocaust. Jewish voices, not gone silent - is heavier now.

Judenstimmen, die nicht schweigen,

Mutter, wie es schallt.

Ich erwach in meiner Wiege,

sonnenschwarz umstrahlt.

In the summer of 1959, Celan, his wife Gisèle, and their 4 year old son Eric visited Sils-Maria in the Engadin region in the Swiss Alps, where Nietzsche spent seven summers.

Tschubby, Creative Commons

Based on the month he spent there, he wrote Gespräch im Gebirge - A Conversation in the Mountains - a sort of folktale, in a conversational tone. The scene is a mountain path, between dusk and nightfall, and an encounter between two Jews, Klein, and his cousin, Gross:

One evening the sun, and not only that, had gone down, then there went walking, stepping out of his cottage went the Jew, the Jew and son of a Jew, and with him went his name, unspeakable, went and came, came shuffling along, made himself heard, came with his stick, came over the stone, do you hear me, you hear me, I’m the one. I, I and the one that you hear, that you think you hear, I and the other one - so he walked, you could hear it, went walking one evening when something had gone down, went beneath the clouds, went in the shadow, his own and alien - because a Jew, you know, now what has he got that really belongs to him, that’s not borrowed, on loan and still owed - so then he went and came, came down this road that’s beautiful, that’s incomparable, went walking like Lenz though the mountains, he, whom they let live down below where he belongs, in the lowland, he, the Jew, came and he came.

So Klein meets his cousin Gross and they start talking, almost oblivious to the beauty of nature all around them, which Celan, nevertheless goes to pains to name: wild flowers like ‘Turk’s cap in bloom, blooming wild, blooming like nowhere, and on the right, there’s some Rampion, and Dianthus superb, the superb pink, growing not far off.’

Turk’s Cap lily (lilium martagon) by Friedrich Böhringer, Creative Commons, wiki/ Rampion (campanula rapunculus): by Hectonichus, Creative Commons, wiki/ Dianthus superb: By Bernd Haynold, Creative Commons, wiki

On the stone is where I lay, back then, you know, on the stone slabs; and next to me, they were lying there, the others, who were like me, the others, who were different from me and just the same, the cousins; and they lay there and slept, slept and did not sleep, and they dreamt and did not dream, and they did not love me and I did not love them, because I was just one, and who wants to love just one, and they were many, even more than those lying around me, and who wants to go and love all of them, and - I won’t hide it from you - I didn’t love them, those who could not love me, I loved the candle that was burning there, to the left in the corner, I loved it because it was burning down, for it was really his candle, the candle that he, the father of our mothers, had kindled, because on that evening a day began, a certain one, a day that was the seventh, the seventh, on which the first was to follow, the seventh and not the last, I loved, cousin, not it, I loved its burning down, and you know, I’ve loved nothing more since then.

What matters throughout Conversation in the Mountains, writes John Felstiner, is how things are voiced and heard. […].

With these ‘cousins’ as Jew Klein calls them, meaning everyone ‘gone down’ in the catastrophe, he ponders his kinship, and the conversation contracts into monologue. […] Owning up to his apartness, Jew Klein finds a voice and something to love. ‘I loved the candle that was burning there…’ […] These words virtually name the Sabbath. When candles are kindled (by a mother) at the close of the week, what seems a burning down, the last of something, turns into a beginning. […] Celan’s recorded voice here has a plaintiveness, that of loss within survival— “because after all here I am.”

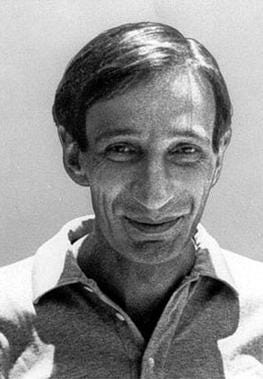

To close this post I’d like to return to Ivan Illich. Throughout his life, as a dissident in the Catholic church, Illich meditated on the parable of the Good Samaritan. Christ set love higher than the law, but the Church made that love into a law, thereby creating a new typer of power. Illich found the roots of modernity in this ‘corruption of the New Testament.’ He made a study, going back to the Middle Ages, of sermons which referred to this parable, and came to a radical conclusion. Jesus’ message was not that ‘we have to love the stranger,’ but rather, that we have the freedom to love him, or abandon him to his death, the wounded stranger, who may be our enemy.

Christianity, Illich told Cayley, brings something new into existence. The Jew could walk, as one old expression says, beneath the nose of God. He could walk in God’s sight and be guided by his word, but the Christian made a new claim: that he could encounter God in Christ and Christ in the unknown one who knocked at his door and asked for hospitality. […]

‘I have spoken to you more than once about what happens to the idea of virtue when it is suffused by the light of the new freedom which allows the Samaritan to step outside his own milieu and pick up that half-dead Jew in the ditch. Perhaps today we would call that Samaritan an intolerable and violent Palestinian, since the point of Jesus’ story was that the one who helped was a foreigner, and even an enemy, to the man in the ditch.’

I read first the poems of Celan and Mandelstam in György Faludy's poetry anthology (Test és lélek). He also inlcuded short introductions of the poets. What a life Mandelstam had:

"MANDELSTAM, OSIP EMILYEVICH (1891 Warsaw –?1938 Siberian prison camp) spent his youth in St. Petersburg, studied at the universities of Heidelberg and Paris, traveled through Italy between 1907 and 1910, then returned to Russia. He joined the so-called "Acmeist" group of poets. According to their own program, the Acmeists set themselves the goal of writing "poems that are of this world, concrete, precise, and architectural." Fifty or a hundred years later, like most poetic schools, this program rings hollow. When asked to define Acmeism in 1937, Mandelstam replied, "It is nothing more than homesickness for world culture."

He published three books of poetry during his lifetime, the last one in 1928. From the 1930s onwards, he was subjected to one attack after another, instigated by the authorities, after he showed no inclination, but even if he had wanted to, he could not have joined Stalin's now forgotten willow poets. A poem he wrote in 1934 about Stalin fell into Stalin's hands; M. was careless enough to circulate it in manuscript form, but "if I don't circulate it, there's no point in writing it. He was arrested and exiled, first to the Urals, then to Voronezh, where he saw the end approaching. After Gorky's death and Bukharin's arrest, there was no one left who might have dared to stand up for him to Stalin. In 1938, he was arrested again. He was last seen in December of that year in a prison camp near Vladivostok, searching for scraps on a garbage heap frozen into a block of ice.

The poems he wrote in the last ten years of his life – almost half of his poetry – were preserved in the memory of his wonderful wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam, who hid them for safety in the soles of old boots, armchairs, and door frames. Nadezhda M. also wrote two profound, memorable, and captivating books about her husband and their life together; the first—and more important—of these was published in English (Hope Against Hope, New York, 1970)."