Exactly a year ago today, on 7 January 2024, Maksym Kryvtsov died on the eastern front in Ukraine, aged 33, fighting for his country against the Russian invaders. His ginger cat, who you can see in this picture with him, was killed in the same explosion.

Maksym was an accomplished poet, and with the permission of his family and of Nash Format publishers in Kyiv, I include the beginning of one of his poems at the start of Chapter 10 - ‘The World Stained Red’ of my own book Walking Europe's Last Wilderness.

Here is the full poem, translated by Larissa Babij:

My head is rolling from grove to grove

like tumbleweed

or a ball

my torn-off arms

will sprout violets in the spring

my legs

will be pulled apart by dogs and cats

my blood

will stain the world in a new red

Pantone Human Blood

my bones

will extend into the earth

creating a frame

my bullet-riddled rifle

will rust

poor thing

my extra clothes and gear

will go to the new recruits

if only spring would arrive

so I can finally

bloom as a

violet.

You can read a 2023 interview with Maksym here:

By giving this platform the title, ‘A Kind of Solution’ I set out to reflect the ambiguity of the world we live in, and to push back a little against those who insist that the world is black and white.

The confluence of the Black and White Tysa rivers, western Ukraine.

Poets living on the edge, facing death each day, understand that better than most. Here is one of his answers:

– In one of your previous interviews you mentioned that God is present at war, likening Him to “charging a machine gun.” Where and in what actions do you find God in such a setting?”

God is most often found in moments of silence. He is the water we carry on missions, which never seems to be enough. There was a time we nearly resorted to drinking from a puddle. He’s in the protein bar you eat while waiting in a trench for the shooting to stop. He’s present in the black, dry sunflowers that offer almost enough cover. But above all, God is in the act of returning.

Which reminds me of the Tom Waits song about a US soldier in Afghanistan:

Here’s a picture of a monument in the western Ukrainian town of Tiachiv to local Ukrainian men who died in Afghanistan between 1979-89. Perhaps the mountains of Afghanistan sometimes reminded them of the Carpathian mountains they grew up in. Note the mountain hat of the soldier sitting down:

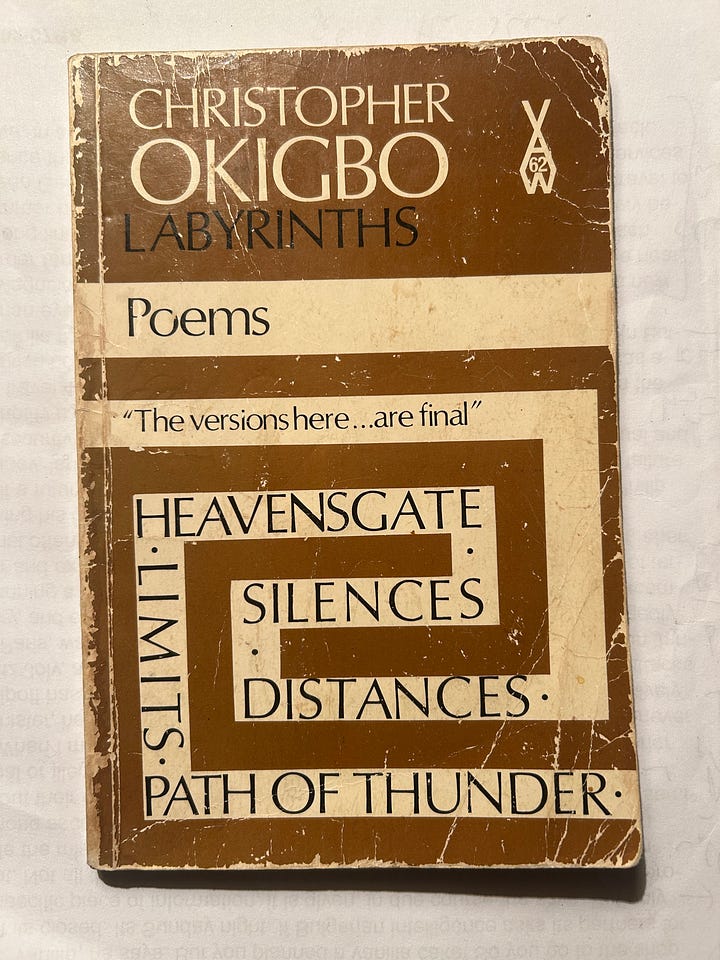

In this text about war poets, I’m going to resist the temptation to quote the British poets of the First World War, like Rupert Brooke, or Wilfred Owen. Instead I will mention Christopher Okigbo, who was killed on the Nsukka battlefront, fighting for an independent Biafra in 1967, aged 35.

From Path of Thunder:

THE ROBBERS are back in black hidden steps of detonators -

FOR BEYOND the blare of widened afternoons, beyond the motorcades;

Beyond the voices and days, the echoing highways; beyond the latescence

Of our dissonant airs; through our curtained eyeballs,

through our shuttered sleep,

Onto our forgotten selves, onto our broken images;

beyond the barricades

Commandments and edicts, beyond the iron tables,

beyond the elephant’s

Legendary patience, beyond his inviolable bronze

bust; beyond our crumbling towers -

BEYOND the iron path careering along the same beaten track -

THE GLIMPSE of a dream lies smouldering in a cave,

together with the mortally wounded birds.

Earth, unbind me; let me be the prodigal; let this be

the ram’s ultimate prayer to the tether...

AN OLD STAR departs, leaves us here on the shore

Gazing heavenward for a new star approaching;

The new star appears, foreshadows its going

Before a going and a coming that goes on forever…

Why do some of us stay and fight, and some of us escape to safety? And if we fight, what are we fighting for, and what are we fighting against? In 2014 I spent a day walking round the military hospital in Kyiv, asking each wounded soldier the same questions: which language would you like to speak to me in (Russian or Ukrainian)? What are you fighting for? And what are you fighting against?

To my surprise, the answer to the first question was invariably ‘Russian’. This war has never been a war between Russian speakers and Ukrainian speakers.

Each soldier gave different answers to what they were fighting for: some said for the Maidan, the pro-EU revolution of 2014, some said simply for their homeland. Others said they had until recently worked on building sites in Russia, where the hourly wage was at that time higher than in Ukraine, and watched the same soap operas as the enemy soldiers. But when it came to what they were fighting against, the answer was always the same: against Putin’s attempt to recreate the Soviet empire, and force Ukraine to be part of that.

On more recent visits to western Ukraine and northern Romania, to research my forthcoming book on the Carpathian mountains, I’ve had a chance to talk to young Ukrainian men who are fighting, and others who decided not to.

You can listen to my 26 minute radio documentary on them here:

The men who do not want to fight

If some of our leaders are corrupt, or if some businessmen are profiteering from the war, in our own or in other countries, should that undermine our willingness to fight?

One of the failings of the Ukrainian authorities has been to provide a civilian alternative to military service.

Since I was a teenager, when I first picked up a book in a shop, I have admired the American anti-war poet Kenneth Patchen.

He raged against the governments, and the military industrial complex, that send men needlessly to their deaths.

Here’s a poem of his, which touches me deeply.

The Fox

Because the snow is deep

Without spot that white falling through white air

Because she limps a little - bleeds

Where they shot her

Because hunters have guns

And dogs have hangman's legs

Because I'd like to take her in my arms

And tend her wound

Because she can't afford to die

Killing the young in her belly

I don't know what to say of a soldier's dying

Because there are no proportions in death.