This evening at the Museum of Ethnography in Budapest, we screened the premier of Bombatér / Bombsite, the first film I’ve made with my son Daniel. The music was composed by my son, Caspar.

After so many years exploring the mountains which ring Hungary, it was a revelation to spend some weeks, in the unrelenting August heat, on the parched flatlands. I found another side Hungary, and the Hungarian character here too. A tough uncompromising resilience.

Our film is one of four commissioned by the museum to celebrate Claude Lévi-Strauss’s idea of Bricolage - Everyday Creativity. This was a concept put forward by Lévi-Strauss in The Savage Mind (1962), recently republished in English with the more politically-correct title, ‘Wild Thought.’ The savage mind, Lévi-Strauss suggested, is much like the ‘civilised mind’ in that we all improvise in order to survive. The only difference is that before the advent of our ‘civilisation’, men and women had to first create their own tools, and improvise with the materials that came to hand. But at the end of the day, we’re very similar. The book helped puncture the idea of ‘white supremacy.’

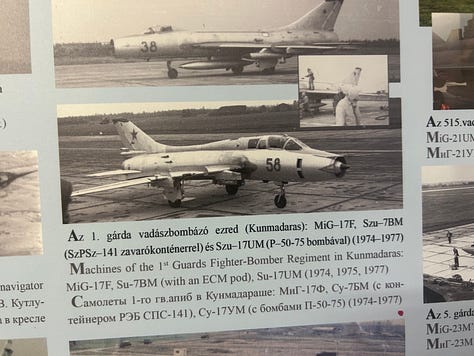

Our film tells the story of Florián and Gyula from Nagyiván, a village on the Hortobágy plain in eastern Hungary. As schoolboys in the 1960s and 70s, they called themselves ‘the partisans’. Every week, from Monday morning to noon on Saturday, Soviet and other Warsaw Pact military planes took off from the biggest Soviet military airbase in eastern Europe, at Kunmadaras, to bomb a 70 km2 section of the Hortobágy National Park, between the villages of Nagyiván and Nádudvar.

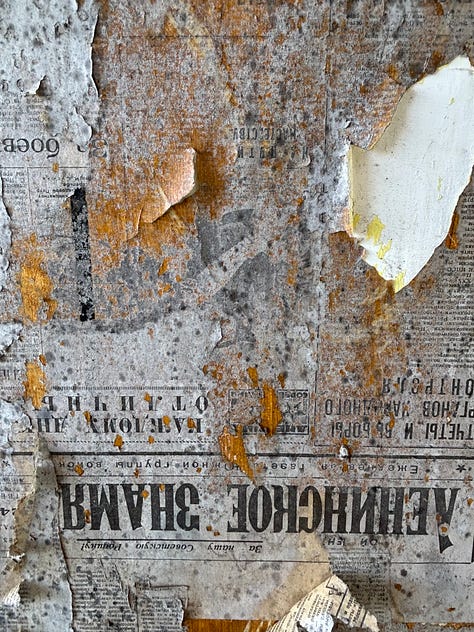

By day and night, the ‘partisans’ raided the bombsite to bring back ‘treasures’ - brass 23 mm rounds from which shepherds made bells for their dogs, high grade steel from which the boys made lifting weights, ‘Stalin candles’ - metal cylinders which fell by parachute, burning magnesium flares, which lit up the sky at night so brightly, you could read a book or newspaper in your yard in the village. The Stalin candles were cut in half for pig’s troughs, or left intact as chimneys. The parachutes were highly prized - the mothers and grandmothers of Nagyiván made duvet covers or curtains from the silk, and found a thousand uses for the strong chords. What the boys didn’t find themselves, the Soviet soldiers sold them - for half a litre of pálinka.

To make sure they got the best pieces, Florián and his mates sometimes spent the night on the bombsite, during the bombing. That meant they could see where the parachutes drifted down.

Their closest shave was when a big one landed, 300 metres from where they were hiding.

‘I remembered my grandfather saying, that if you keep your mouth open, the blast won’t destroy your ear drums…’ said Florián.

The bombsite was cleared of debris by the Hungarian army between 2016 and 2020. Four Hungarian soldiers lost their lives when one exploded. Florián’s godson was killed when he tried to cut through a live round. Another boy had enough of life, and wandered away into the bombsite, and was never found.

Many of the bombs the army cleared are on display in the remarkable museum in Berekfurdö: Soviet airforce museum.

The Kunmadaras airbase, with its 2.8km long runway, is now overgrown with sloe bushes and trees. When we filmed there in August, the sunflowers nodded their heads in sharp lines where troops once paraded. Sloes grew fat on the bushes. The guard at the gate told us that a Russian woman came back, only last summer, and told him that the happiest years of her life were spent here, where her husband was an airman, and her daughter was born. Nowadays, owls and bats have taken over the control tower and the hangars. In one, thousands of winter overalls of the Hungarian military have been dumped.

One of my favourite phrases in Hungarian is ‘behind God’s back’, meaning ‘the back of beyond.’ But there’s nowhere to hide on the Hortobágy plane, from bombers or from God. This is rather, as I mention in the film, ‘God’s forehead.’ Soon after we recorded that sequence, we came across the following, quite by accident, among Sándor Petöfi’s Úti Levelek (notes from the road), dated 14 May 1847: Hortobágy, dicsö rónaság, te vagy az Isten homloka/ Hortobágy, praiseworthy plain, you are the forehead of God.

Today, wild birds and frogs have recolonised the craters of the bombsite. Herds of grey cattle and sheep graze here. The most destroyed place is now one of the most strictly protected.