My Syrian friends are weeping with joy. Bashar al-Assad, the man who seemed so civilised when he came to power in 2000, but whose regime turned brutal, then mass-murderous, is out. His soldiers melted away, rather than defend him. His foreign backers, Iran and Russia, failed to even try to rescue him. Syria has been engulfed in a wave, no, an ocean of euphoria. My friends tell me the latest news, then rush out onto the streets of Europe, in those countries which were generous enough to give them shelter, to celebrate the fall of the tyrant with their fellow Syrians. Some are already talking about going home, to rebuild their ruined country.

Aynass and her children Maria, Issam, and Suhaib - in Sweden, 2024

The sudden fall of the Assad regime reminds us all how brittle power can be. ‘It takes only 3,000 people to make a revolution’, Miklós Vásárhelyi, press secretary to the Hungarian Prime Minister Imre Nagy during the 1956 revolution in Hungary, once told me. As I witnessed the fall of one Communist regime after another in the miraculous autumn of 1989, and the fall of Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia in the autumn of 2000, I often pondered Miklós’s words. And now Assad. But which 3,000 people, and when?

I also remember a Syrian rebel soldier, quoted in the Guardian, sometime in 2013 or 2014, when the rebel cause against Assad had run out of steam.

‘We are not fighting for or against anyone anymore,’ was the gist of his words. ‘We are just fighting to avenge our comrades who have been killed.’

In October 2015 I asked a Syrian asylum-seeker, on the Hungary-Croatia border, what he thought about the fact that the Russians had just started bombing his country.

‘It’s strange isn’t it? Everyone says they want to help us, by bombing us.’

If that is the nature of war, what is the nature of power?

Aynass and the children, somewhere in the Balkans, 2019

In 1989, what looked like the powerful reinforced windscreen of Communist rule in eastern Europe, struck by a few pebbles or scraps of grit, shattered into ten thousand pieces. No-one saw that coming, either. I remember conversations with British, German, and US diplomats between 1986 and 1989. Everyone was trying to guess which Communist apparatchik would replace János Kádár in Hungary, or the other tough old men in the region. The money in Budapest was on Károly Grósz, a now forgotten figure. No one imagined the whole regime would be swept away.

Of course, it’s easy to understand in retrospect how it happened. Mikhail Gorbachev pulled the carpet out from under the feet of an ossified elite. The ‘lull’ in Marxism which the head of the agitation and propaganda department, János Berecz lamented, was not so much a lull, as a vast chasm of disbelief. The regimes were burnt out, untalented, held together by men and women chosen for their loyalty, not their capabilities. The strength of reviving patriotism, the flight of east German refugees through Hungary, the acts of witness and oratory of dissidents, the bloody-mindedness of Polish shipyard workers, the unquenchable bravery of the youth, the disenchantment of the population with regimes which destroyed the environment with unwieldy hydro dams, or factories belching cancerous fumes, all combined in a perfect storm which toppled regimes no longer held up by Moscow. A group of psychology students at the Charles University in Prague set up an impromptu ‘citizens’ advice bureau’. One of their first customers was a man who told them in a serious voice that the Central Committee of the Communist Party had planted a controlling device in his brain, and asked them to remove it. Hopefully, they managed.

Since 1989, many conspiracy theories have emerged about which great men engineered the revolutions from far away. But I believe to this day that those were genuine popular uprisings, a revolution or series of revolutions. The fact that revolutions always seem to get hijacked, sooner or later, doesn’t mean they were not revolutions in the first place. The people, everywhere, and always, want to be free.

Aynass’s home city, Douma, 13 km from the Syrian capital; Damascus, in 2018.

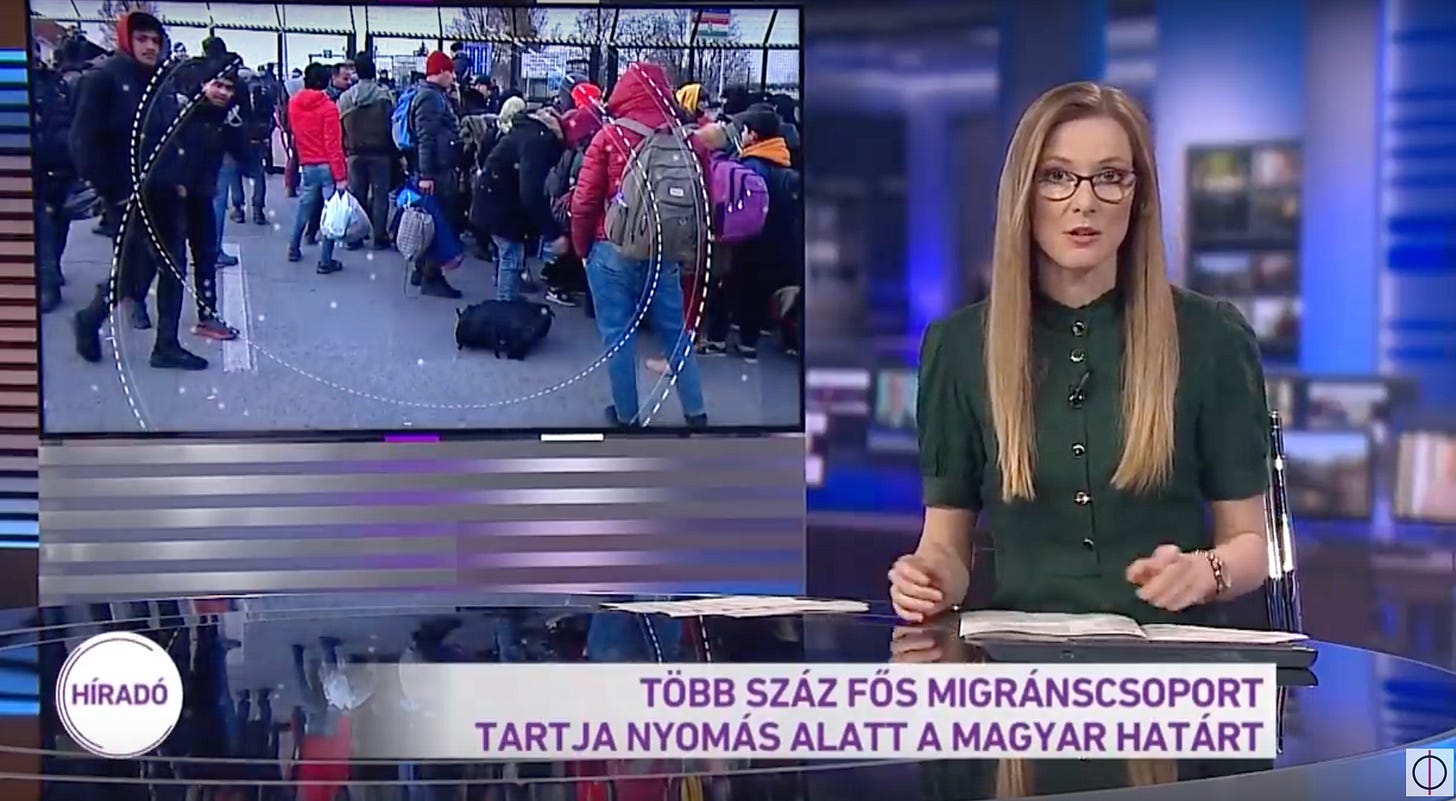

In 2019, after losing her husband in the war, Aynass decided to flee. It took more than a year on the road with her three children, then aged 15, 11 and 6, to reach Sweden, where her mother and father and two brothers had already found refuge. I first got in touch with her in Serbia, where she and the children spent 6 months in a refugee camp, looking for a legal way to continue their journey. There were no legal ways. As an act of despair, she and the children were among a group of several hundred migrants who walked from the city of Subotica to Kelebia on the Hungarian border, in February 2020. Here is a screenshot from the M1 news that evening, a channel controlled by the Hungarian government. The headline reads: ‘Group of several hundred migrants are putting pressure on the Hungarian border.’ Poor old border.

By 2020, Hungary had stopped giving asylum to anyone. Very few actually wanted to go to Hungary anyway, but it was and is an important transit country, on the way to western and northern Europe. Aynass and her children crossed on foot from Serbia into Romania, from Romania into Hungary, and from Hungary all the way to Sweden, in the summer of 2020. ‘We walked so much,’ she told me, ‘my feet grew from size 37 to size 38!’

A map drawn by inmates at the Nyírbátor migrant detention facility in Hungary, 2018

In Sweden they got asylum. The two boys, now 11 and 17, have already been granted Swedish citizenship. Aynass and her daughter Maria are still waiting for theirs. Aynass is doing a masters degree at a university in southern Sweden, to allow her to finally continue her former profession, as an English teacher.

Here is an extract from a phone interview I did with her yesterday, on Sunday 8 December 2024 - the first day of Syrian freedom.

As Aynass says, huge challenges lie ahead. And massive decisions. The first thing her children asked her, when they heard the news from Damascus was: ‘does that mean we can go home now?’

Before the civil war, in 2011, the population of Syria was 23 million. Around half a million are believed to have died in the war. Half the population had to flee their homes, some to other parts of Syria, millions abroad, to Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, and beyond. Many countries made them welcome. The granting of temporary or permanent refuge is one of the ways that we prove we are not barbarians. And one day, if they are lucky, refugees can go home.