'To Change the World...

...we must first change the way babies are being born'

wrote Michel Odent, the celebrated French surgeon and champion of undisturbed birth, who died on 19 August in London, aged 95. It seems useful to ponder birth at a time when we are so mesmerised by death: in Gaza, in Utah, or in all the other places on the planet where it happens, every minute of every day, and no reporter is there to record or report the name of the child or adult who just died, unnecessarily, or why.

Michel Odent in Budapest, 30.04.2022 - photo by Tamás Koos

Michel dared to connect the way we are born, and our first days and weeks of life, to the happiness and calm, or the violence of the world we share with others. He wrote, and talked, at every opportunity about the dignity of the woman in labour. You can find links to his work and views here or here or here.

In his later books, he pondered the future of a world where the experience of birth has been stolen from women for so long, that they might forget how to do it. And where so many medical professionals have never witnessed a natural birth, they insist on inducing and controlling the process, because they would not know what to do, or not to do, if it happened naturally. We have industrialised and ‘masculinized’ birth, he believed, to our own vast impoverishment.

‘…childbirth is the phase of human life that has been the most dramatically modified, during the past decades, at a planetary level. In the age of cheap synthetic oxytocin and simplified techniques of cesareans, the number of women who give birth to babies and placentas thanks to the release of a ''cocktail of love hormones'' is suddenly becoming insignificant.’

He pushed for more discussion of birth, in a world obsessed with abortion. These are delicate subjects, especially for a man to wander through, so I will try to tread carefully.

Me and my son Máté, at a Homebirth conference with Michel Odent, Budapest, early summer 1995. Photo by Ágnes Geréb.

“Experiences have clearly shown that an approach which ‘de-medicalizes’ birth, restores dignity and humanity to the process of childbirth, and returns control to the mother is also the safest approach,” he wrote.

I met Michel several times, on each of his visits to Hungary. He came to support Dr Ágnes Geréb, a brave Hungarian obstetrician turned midwife, and the small circle of midwives, doulas and us parents, struggling to convince a suspicious, powerful, and sometimes corrupt obstetric profession to surrender some of their power over childbirth to mothers. And to restore the much-degraded profession of midwifery.

Neither he, nor we, ever questioned the value of medical intervention where medically necessary. But we all opposed a culture of intervention, where one drug or cut leads to another.

Michel first came to Hungary in May 1992 to the first Homebirth conference in Szeged, in the early, heady days of freedom after the fall of Communism, when central authority seemed weaker, and people felt freedom on their skins, and dared think about what that might mean. I met him again in 1995, by which time my second son, Máté was born.

Máté returning a stranded lamb to its mother, Huascaran national park, Peru, March 2025

Michel’s life work, his 17 books, translated into 22 languages, and countless lectures and interviews, was dedicated to reminding women that they actually know how to give birth, if everyone else would stop disturbing and distracting them. And that the time from conception, through birth, and the first months of life, leave an indelible impression on us, and on our immune systems. So they also have a discernible impact on the society we live in. It is a simple, powerful argument. More undisturbed births breed healthier, less disturbed societies.

Such births are safer, and empower women, he wrote. Likewise, if our births are crowded by unnecessary attendants, medical students, relatives, friends or medical students, brightly lit, and induced, there is more likelihood that we will become frustrated, unhappy, even violent individuals. Obstetricians tell mothers that each intervention is just for their own safety, and that of the newborn. When often, it is to make sure that babies are not born at weekends, when obstetricians like to rest, or during their winter holidays, when they like to ski.

According to data from the Central Statistical Office (KSH), the number of births goes up steeply on Fridays and Mondays, down at weekends, and sinks further on public holidays like Christmas and the New Year. Birthing, it seems, fits into the hospitals’ and the doctors’ schedules. ‘However much money you offer couples to have more babies…’ I once told Katalin Novák, when she was Families Minister in the Orbán government, ‘they won’t have a second or third, if their first experience was miserable.’

Stills from the film Vigilance, TintoFilms, Budapest 1997.

The ideal birth Michel wrote, provocatively, sees the woman alone in a small, dark room with a silent, experienced midwife knitting in the corner. Knitting, he emphasised, because through that simple, thoughtless, repetitive action, the midwife does not communicate fear, or adrenaline, to the birthing woman. Controversially, Michel liked to discourage male partners from attending the birth of their children, because there was a high likelihood that they would interrupt or slow down the birth.

This was always a little difficult for me to swallow, as a father who attended the births, at home, of all of my five sons. Each time I felt useful and supportive, and immensely fortunate to witness the beginning of life, and establish my own bond with my boys, in their first seconds on earth. ‘Was I actually useful, though?’ I asked my wife, as I prepared this post. ‘You were…’ she replied, re-assuringly. Then thought a bit. ‘Not so much at the fifth birth…’ she added. A female friend was also there then, to whom she was very close, as well as our midwife, Ágnes. ‘And it felt like a very female time. So your presence did feel strange.’

Michel was already a surgeon at the dawn of the age of caesarean sections. He became an obstetrician ‘by accident’, he told an interviewer.

‘It was in the 1950s, when they first developed the modern technique of the caesarean section. Obstetricians had no experience with surgery. At that time, c- section was in the category of emergency surgery. And I experienced the technique in the French army, in 1958 and 1959 during the war in Algeria.’

He took over the maternity unit at Pithiviers, south of Paris, and ran it from 1962-85. There, he encouraged women to sing and shout while they gave birth, discussed ways to better manage pain in childbirth, trained midwives to attend births with no doctor present, and introduced birthing rooms and birthing pools. He explored and explained the impact of the immediate environment on the birth process. His reputation spread rapidly, and women flocked there to give birth.

Though skilled with the scalpel, he worked to reduce its necessity, going against the flow of a world in which C-section rates have soared.

Recent data (2021) illustrate this: Cyprus: 54%, Romania: 44.1%, Poland: 42.2%, Hungary: 34.6%, UK 34%, Italy: 32.3%, Germany: 30.7%.

Brazil has the highest in the world with 57% (30% in public, 70% in private hospitals).

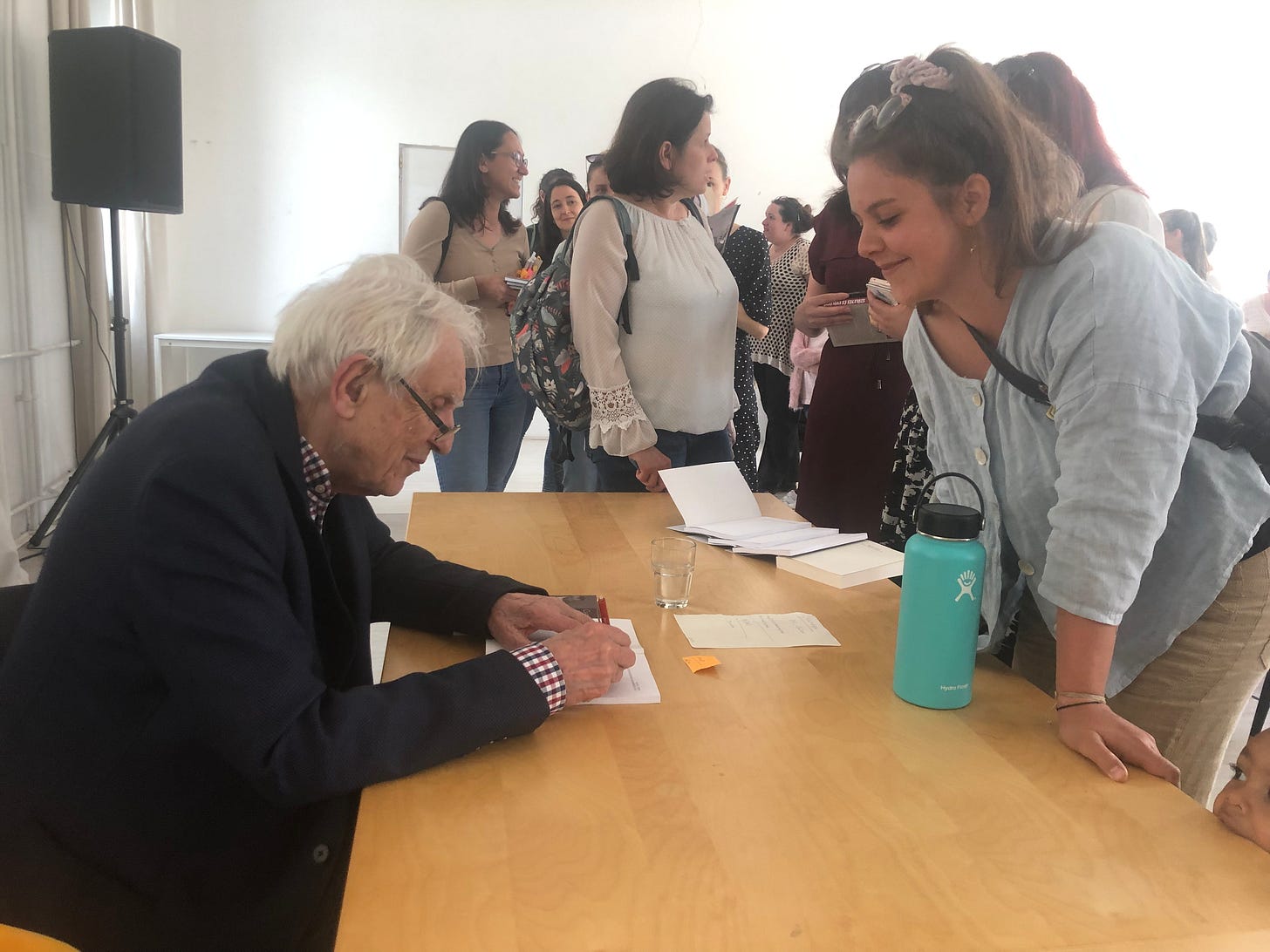

Michel signing books in Budapest, 30th April 2022, picture Nick Thorpe

One friend who gave birth recently in Hungary had a C-section because the doctors said the baby was too early. Another because the doctors said it was too late. Both were young, healthy women, giving birth for the first time.

‘De jó hogy túl vagyok rajta…’ - ‘What a relief, to have got that over with…’ was a common refrain from postpartum women, when I took part in a campaign in Hungary, published in the Népszava daily in 1997 called ‘Méltó módon szülni’ - To Give Birth in a Dignified Way’. Our campaign was modelled on a similar initiative in Poland, led by the Gazeta Wyborcza daily which began in 1994 ‘Rodzić po Ludzku.’

‘The point is not how to reduce the rate of c-section, it is how to improve our understanding of birth physiology, how to think in a positive way,’ Michel said.

He coined the term 'primal health' to describe the sensitive period from conception to the first year of life. He argued that our lifelong health and even our capacity for love are shaped in this period. He founded the Primal Health Research Centre in London and created a database linking perinatal experiences to long-term health outcomes.

Michel Odent was due to visit Hungary again this summer. Here is an extract from his last email to Ágnes Geréb, to whom I am grateful for permission to quote it here:

My dear Agnes,

I suggest we start with only one question:

"What do we know about the maternal, placental and foetal physiological processes interrupted by labour induction?"

Love

Michel

I remember my mother’s story of my own birth, at home, in the village of Upnor, Kent in 1960. ‘I sent your father off to find a doctor,’ she said, ‘so I could get on with the birth, accompanied by a very reassuring, and rather large midwife.’

With my parents and sister Mish, Summer 1960

So I was born, she used to say, ‘just in time for lunch.’

Chapter 11 of my book ‘89 The Unfinished Revolution - Power and Powerlessness in Eastern Europe takes my experience of childbirth in Hungary as example of the freedom, and authoritarianism of the first 20 years of democracy. .

Dear Nick,

I completely agree that women should give birth in the most natural way as it possible, but I think the most important thing for a woman giving birth is self-confidence. Women need to believe in themselves, want to be there, and want to give birth to their child. Because that (and abdominal muscles) is the key to a calm, healthy birth. I gave birth with a doctor's assistance, and for nine months I had prepared myself to "do it and be able to do it without anesthesia." I was given oxytocin after 10 hours of labor because the doctor saw that I was tired, and at that point, the pushing pains hadn't even started. To this day, I am grateful to the doctor for giving me oxytocin at the right time, because even now, 10 years later, I remember the birth of my son as the most wonderful day of my life. Even though it took 45 minutes to stitch me up. That euphoric feeling when I held my son in my arms was one of the most beautiful moments of my life, and I don't remember the pain at all (thanks to natural hormones). According to the doctor, if my baby had been 20 decagrams heavier, I would not have been able to give birth naturally. My husband's presence meant a lot to me. I needed him to be there with me so we could bring our little boy into the world together. In short, I support natural childbirth, but many mothers don't believe in themselves, and that's when doctors play a huge role.

All my respect to you and your wife for raising five children! :)

Beautiful. The photos as well. How lucky you are that your children were born with Ágnes by the mother's side!